- Home

- Nibedita Sen

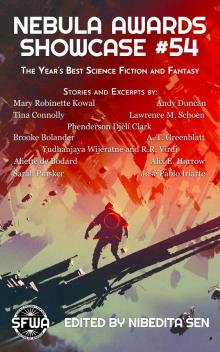

Nebula Awards Showcase 54

Nebula Awards Showcase 54 Read online

NEBULA AWARDS SHOWCASE #54

The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy

Edited by Nibedita Sen

Copyright © 2020 by Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Inc.

EPUB Edition

Introduction copyright © by Nibedita Sen

“It’s Dangerous to Go Alone” © by Kate Dollarhyde.

“Into the Spider-verse: A Classic Origin Story in Bold New Color” © by Brandon O’Brien

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder.

ISBN 978-0-9828467-3-5 (print)

ISBN 978-0-9828467-4-2 (ebook)

“The Secret Lives of the Nine Negro Teeth of George Washington” by Phenderson Djèlí Clark, copyright © 2018 by Phenderson Djèlí Clark. First published in Fireside Magazine, February 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Interview for the End of the World,” copyright © 2018 by Rhett C. Bruno. First published in Bridge Across the Stars, edited by Chris Pourteau and Rhett C. Bruno, 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“And Yet,” by A. T. Greenblatt, copyright © 2018 by A. T. Greenblatt. First published in Uncanny Magazine, 3-4/2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies,” by Alix E. Harrow, copyright © 2018 by Alix E. Harrow. First published in Apex Magazine, Feb. 6, 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Court Magician,” by Sarah Pinsker, copyright © 2018 by Sarah Pinsker. First published in Lightspeed Magazine, Jan. 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Only Harmless Great Thing,” by Brooke Bolander. Copyright © 2018 by Brooke Bolander. First published by Tor.com, 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Last Banquet of Temporal Confections,” by Tina Connolly. Copyright © 2018 by Tina Connolly. First published by Tor.com, 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“An Agent of Utopia,” by Andy Duncan. Copyright © 2018 by Andy Duncan. First published in An Agent of Utopia: New and Selected Stories, 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Substance of My Lives, the Accidents of Our Births,” by José Pablo Iriarte, copyright © 2018 by José Pablo Iriarte. First published in Lightspeed Magazine, January 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Rule of Three,” by Lawrence M. Schoen, copyright © 2018 by Lawrence M. Schoen. First published in Future Science Fiction Digest, December 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Messenger” by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and R.R. Virdi, copyright © by LMBPN® Publishing. First published in Expanding Universe, Volume 4, 2018. Reprinted by permission of LMBPN® Publishing.

Excerpt from “The Tea Master and the Detective,” by Aliette de Bodard. Copyright © 2018 by Aliette de Bodard. First published by Subterranean Press. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Excerpt from “Fire Ant,” by Jonathan Brazee. Copyright © 2018 by Jonathan Brazee. First published by Semper Fi Press. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Excerpt from “The Black God’s Drums,” by P. Djèlí Clark. Copyright © 2018 by P. Djèlí Clark. First published by Tor.com Publishing. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Excerpt from “Alice Payne Arrives,” by Kate Heartfield. Copyright © 2018 by Kate Heartfield. First published by Tor.com Publishing. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Excerpt from “Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach,” by Kelly Robson. Copyright © 2018 by Kelly Robson. First published by Tor.com. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Excerpt from “Artificial Condition: The Murderbot Diaries,” by Martha Wells. Copyright © 2018 by Martha Wells. First published by Tor.com Publishing. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Excerpt from “The Calculating Stars,” by Mary Robinette Kowal. Copyright © 2018 by Mary Robinette Kowal. First published by Tor Books, 2018. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Cover Design by Lee French and Lauren Snow

Designed by Emily Mah Tippetts

Formatted by BB eBooks (bbebooksthailand.com)

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introduction by Nibedita Sen

“It’s Dangerous to Go Alone” by Kate Dollarhyde

“Into the Spider-verse: A Classic Origin Story in Bold New Color” by Brandon O’Brien

“The Secret Lives of the Nine Negro Teeth of George Washington” by P. Djèlí Clark

“Interview for the End of the World” by Rhett C. Bruno

“And Yet” by A. T. Greenblatt

“A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies” by Alix E. Harrow

“The Court Magician” by Sarah Pinsker

“The Only Harmless Great Thing” by Brooke Bolander

“The Last Banquet of Temporal Confections” by Tina Connolly

“An Agent of Utopia” by Andy Duncan

“The Substance of My Lives, The Accidents of Our Births” by José Pablo Iriarte

“The Rule of Three” by Lawrence M. Schoen

“Messenger” by R.R. Virdi & Yudhanjaya Wijeratne

Excerpt: “The Tea Master and the Detective” by Aliette de Bodard

Excerpt: “Fire Ant” by Jonathan P. Brazee

Excerpt: “The Black God’s Drums” by P. Djèlí Clark

Excerpt: “Alice Payne Arrives” by Kate Heartfield

Excerpt: “Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach” by Kelly Robson

Excerpt: “Artificial Condition: The Murderbot Diaries” by Martha Wells

Excerpt: The Calculating Stars by Mary Robinette Kowal

Biographies

About the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA)

About the Nebula Awards®

Introduction

These are strange times in which to be writing the introduction to a collection of speculative fiction. Apocalyptic times, some might say. I’ll spare you a summary of these anxious, pandemic-wracked months; you’ve lived them just the same as I have, and I doubt they’ll be gone from your memory by the time this collection comes out. I doubt, in fact, that the scars will be fading from our collective and individual consciousnesses any time soon.

In these strange times, many science fiction writers are discovering just how unnervingly prescient their work turned out to be. Yet others are bemoaning the realization that they held back for no good reason—that they could have made their villains more cartoonishly evil, more outrageously nonsensical and self-centered, but refrained for the fear that (yes, the irony stings) it wouldn’t be believable.

They say truth is stranger than fiction. Maybe it’s just that we hold fiction to higher standards, while reality is spared the same quality assurance.

If nothing else, it’s safe to say reality is considerably more taxing than fiction, these days.

It’s hard to create in times like these. It’s hard to bring tender new things into a world that’s on fire under the best of circumstances, let alone when all our resources are devoted to simply treading water. If you’re not creating things right now, you’re not alone, and also, it’s okay. Your value isn’t defined by the words and the work you put out into the world; you matter, and you’re allowed to protect yourself.

But, ironically, these times that make it hard to make art also prove to us just how necessary art is. Every TV show and book and movie and game that keeps us sane and emotionally nourished throug

h this isolation, confinement, and anxiety is a testament to what stories do and why they matter. Stories have a terrible and fearsome power, and if you need more evidence, just turn on the news (or, mental health depending, don’t). The people in power tell us stories every day—stories that serve their agenda and twist the truth, stories that harm the vulnerable and protect the privileged. The stories we tell each other in response are more important now than they’ve ever been before.

And speculative fiction? Well, I may be biased, but I think speculative fiction has a power all its own. I survived an MFA; I know far too well how the establishment likes to write us off as frivolous or insignificant because we engage in the business of inventing things that aren’t real. But when truth is stranger and more incomprehensible than fiction, inventing things can become a way to speak truth to power.

I said earlier that current events are proving a lot of writers prescient, but it would be a mistake to get too hung up on science fiction’s ability to accurately predict the future. Its real power is to influence that future by speaking to our present, using the lens of a potential future—or an alternate history—to shine light on the here and now. Fantasy wields the same, strident language of possibility when it imagines worlds both like and unlike our own, giving voices and faces to those whom history tried to overwrite, giving them teeth and weapons with which to bite back, or even just giving them much-deserved joy. Speculative fiction is political—always has been. It’s a blade and a beacon and a microscope and a telescope, and metaphors aside, it’s a field I’m never not proud and enthralled and excited to be working in.

The truth is that it’s never more important to be able to imagine different realities than when the one you’re living in is full of despair. The truth is that the most marginalized of us are the ones most often in need of a little magic, whether that takes the form of hope or revenge or bloody catharsis, and even if people try to smack it down as ‘escapism.’ There’s nothing wrong with a little escape. At the risk of quoting one of the dinosaurs we’re moving beyond, “Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?”

And, as it so happens, the writers most disadvantaged by the status quo are often the best at bloodying or escaping or reimagining or uplifting it, since they’re not invested in maintaining it. I spared you a summary of the pandemic; I’ll skip recapping the Puppies, too, and just say instead that the pushback we’ve seen against diversity in the SFF industry is commensurate with a sea change in the way that industry works. One look at this TOC is proof enough, and if you need more, just look at the 2019 nominees too. We’re living in a new golden age of SFF, and the brightest lights in our sky are queer, women, people of color, disabled, and neurodivergent—all the people who fell through the cracks. We’re climbing back out, and we’re changing things.

And we’ve got a long, long way to go.

The world we live in is broken—but, as Rumi said, the crack is how the light gets in. And what a luminous sea of stars we’re floating in. Just look at this TOC—it’s radiant.

I can’t wait to find out what stories the future holds.

~Nibedita Sen

It’s Dangerous to Go Alone

by Kate Dollarhyde

In a November 12, 2018 piece in GeekWire, titled “First-ever Nebula award for game writers approved by professional science fiction writers organization,” Frank Catalano, summarizing the words of then-SFWA president Cat Rambo, wrote that it took, “three tries in three different decades” for the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America to welcome game writers into the organization.

As a writer and editor straddling the fields of speculative fiction and game development, I wasn’t surprised to read that anecdote. For a genre that has at times considered itself the vanguard of narrative innovation, speculative fiction occasionally finds its growth hidebound by convention, and so I suspect some of my peers in the genre struggled to see the relevant connections between game writing and prose fiction.

I can’t exactly say I blame them, because the differences between writing novels, short stories, and video games are significant. While game writing is necessarily writing, the methods by which players encounter that writing—and the means by which that writing is produced—bear little resemblance to the familiar processes of prose fiction.

A game’s script is often designed to support rules, art, and gameplay. The pursuit of fun or challenge may trump story, theme, character, or the poetry of language. Game writing is frequently a team sport, involving the work of anywhere from one to twenty writers—or more. Scripts are often highly collaborative constructs, touched by designers, scripters, and, if we’re lucky, editors, thereby muddying any chance a player may have had at attributing sole authorship. The experience of writing a game can sometimes be as alienated from writing novels and short stories as I expect one can find while still being called fiction writing.

Yet, games don’t need to transcend their constraints to tell immersive, personal, and introspective stories, because when a player interacts with a game, the game interacts back. This push-me-pull-you dynamic is often a carefully crafted illusion, but it can make games powerful tools for inspiring empathy, challenging beliefs, and provoking action. Some of the most exciting work in the field—work like Outer Wilds, Mutazione, Tacoma, and Kentucky Route Zero—leverages strengths specific to the medium to make thematic arguments and tell their stories in ways only games allow.

There’s an impulse in us to treat contemporary iterations of play as something new, but the truth is that speculative fiction and games have long cross-pollinated. Gary Gygax, in his first edition of the Advanced Dungeon & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide, published in 1979, noted the influences of Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. P. Lovecraft, Fritz Leiber, Roger Zelazny, and Michael Moorcoc. Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck’s Expanse series of novels begin as the setting of a tabletop role-playing game Franck had run for several years prior. Disco Elysium, groundbreaking detective RPG released by ZA/UM in 2019, claimed Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, authors of Roadside Picnic, as significant inspirations, as well as the work of Dashiell Hammett and China Miéville, particularly the latter’s novel The City & The City.

Many professional speculative fiction writers are also game writers, and vice versa. Alyssa Wong (author of award-winning short story “Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers”), Patrick Weekes (author of the rip-roaring Rogues of the Republic series), Carrie Patel (author of the Recoletta series), and Cassandra Khaw (author of Hammers on Bone) are all game writers. And they are certainly not alone—in this hustle or die economy, many of us must juggle several professions just to survive. Opportunities for writers to work in both games and traditional fiction continue to grow; sub-Q, a magazine of interactive fiction, is now a SFWA-qualifying market, having published Monica Valentinelli, Ken Liu, Porpentine Charity Heartscape, Nin Harris, and many others. Choice of Games, a developer of text-based games, has published speculative fiction authors Max Gladstone, Kate Heartfield, Darusha Wehm, and Natalia Theodoridou, again among many others.

In recognizing games as a meaningful media for storytelling, SFWA acknowledges a history of labor and collaboration long present in the genre—and in a broader sense, they recognize a truth that’s been with us for at least four thousand years: our games are as much devices of storytelling as our stories are. We’re not acknowledging something new, then, but returning to our roots. It is not an act of magnanimity but one of formally honoring those who have long shared the same table.

However, game writing is bigger than one award can really contain; just as the Nebulas have been subdivided to recognize novels, novellas, novelettes, and short stories to give writers in those forms a fair shake, we must recognize that we could do the same for games, because games are as varied a storytelling medium as prose fiction. The work being done in the field is as variable as the people who develop it; to

generalize as if their resources, goals, or audiences are same, or similar—or that they even want to be—is to do the field a grave disservice.

Consider the game stories recognized by game developers and players as award-worthy in 2018. The 2018 XYZZY Awards, an event celebrating interactive fiction, awarded Best Writing to Animalia and Bogeyman. The Independent Games Festival awarded Best Story to Night in the Woods. The 2018 British Academy Game Awards recognized God of War as having the Best Narrative. Animalia and Bogeyman were written and developed by individuals, Ian Michael Waddell and Elizabeth Smyth respectively, in a freeware narrative flowchart tool called Twine. Night in the Woods was developed by Infinite Fall, six people working in the subscription-based game engine Unity. God of War was developed by more than two hundred people at Sony Santa Monica, a studio owned by Sony Interactive Entertainment, using a proprietary engine developed in-house specifically for that title.

These teams’ resources were not equal, their goals were wildly divergent, and the audiences they were trying to reach could not be more different. Yet they’re all games worthy of recognition for the strength of their storytelling. As this award category matures, how are we to judge quality, innovation, and execution of a storytelling mode with the potential to function in a manner so alien from the familiar, when the perspectives these stories are operating from and the resources available to them are so different?

I suggest that the answer is to ask first and always: what moves you? Begin there and go forth, because a culture rooted in joy, collaboration, challenge, and innovation awaits you. Meet this culture as it is, and understand: there’s always more work to be done—and there’s room for you, too, if you want to help see it realized.

Into the Spider-verse: A Classic Origin Story in Bold New Color

Nebula Awards Showcase 54

Nebula Awards Showcase 54